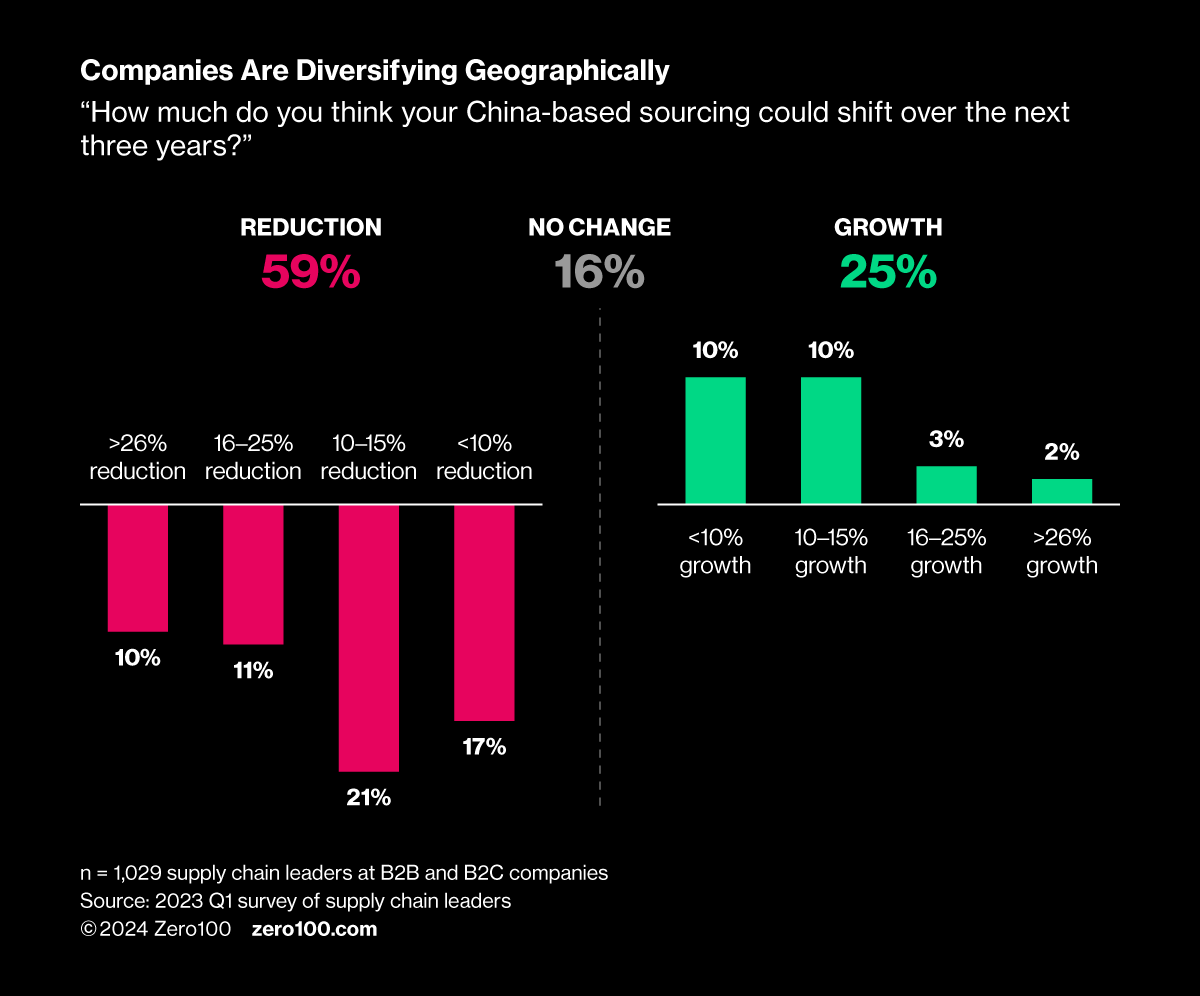

Regional Supply Chains Offer More than Just a De-Risking Opportunity

Shifting manufacturing out of China isn’t just about de-risking operations. Going forward, resilient and regionalized supply chains will spend less energy moving stuff and more energy making the right stuff in the right place at the right time.

A recent WSJ article threw shade on the idea that moving manufacturing away from China is a good way to de-risk supply chains. It was a catchy, contrarian piece challenging the shift toward supply chain regionalization, but I think it misses the practicalities of designing supply networks for the future.

Taking the First Step

The article cites 2023 research from the Bank for International Settlements (BIS), which uses company-level data on supplier-customer pairs to show that US-China trade has fallen since 2021 while US trade with Southeast Asia has increased. The authors posit that countries seeing a big uptick in US trade, like Vietnam, have “interposed” themselves in the chain but are still dependent on China, according to the same data. The implication is that this extra “distance” (not miles per se, but “linkages”) adds complexity and, therefore, risk.

Does this mean supply chain leaders should skip the whole idea and just keep all their eggs in the China basket?

No, but it affirms the fact that some essential upstream inputs like semiconductors, metals, resins, and fabrics made primarily or exclusively in China will be slow and expensive to replace. This is the crux of a detailed piece of investigative reporting by Patrick McGee of the Financial Times on Apple’s slow-motion move to scale iPhone production in India as a de-risking move away from China.

The practicalities of that story highlight what’s really happening, which is that manufacturing partners for big brands like Apple, Adidas, and Hasbro have long produced in China but also in other countries. Companies like Pou Chen, Foxconn, and Tomy Ltd. will invest in new geographies that make sense for their customers and for their own costs. The business relationship often remains the same, but the plants, jobs, and materials move as needed.

Shifting volume to countries that want to attract manufacturing investment, like India, Vietnam, Indonesia, and Mexico, usually starts with assembly operations, which then often drive upstream investment in component or raw material production. Government support with tax breaks, public infrastructure investment, and educational improvements take time to work, but they create the foundations for growth.

Vietnam may be “interposing” itself into your supply chain, but the goal is to earn your business for the long term, and assembly is just the first step.

Closer to Customers Is Better

The race to the bottom for low-cost labor, kicked off by China joining the WTO, saved customers money for a long time. Now, however, as supply chain leaders build regional supply networks, the point is not only about the lowest possible cost but also the right product mix for each market and accommodation of local regulations and logistics infrastructure.

Investments by global companies like Ecolab in Vietnam and Baker Hughes in Singapore are meant to better support the needs of local customers like McDonald’s and Shell with in-country production that is closer, faster, and less shipping-dependent.

Consumer brands, too, like Colgate-Palmolive, L’Oreal, and Estée Lauder, generally produce in-country-for-country, in part because local suppliers are often better suited to meet regional customer tastes. In the extreme, factory-in-a-box examples from innovators like Nokia, GE Healthcare, and Southeast Grocers take this trend even further by getting as close to customers as possible, trading scale and low unit cost for responsiveness and customer-centricity.

Sustainability Counts Too

The BIS study left the impression that diversifying away from China is paradoxically lengthening supply chains. The practical truth is that business leaders are pushing for supply chains that source, make, and deliver with as little long-distance transportation as possible. Risk is certainly important, as the latest problems with Red Sea attacks have shown, but the bottom line is that long-haul shipping is costly, time-intensive, and carbon-heavy.

A manufacturing site in Vietnam or Mexico means that at least some goods are one step closer to delivery as work-in-process inventory, traveling fewer miles as finished goods. And it’s even better when suppliers step up to serve those sites with locally produced input materials. In time, regionalized supply chains will spend less energy moving stuff and more energy making the right stuff in the right place at the right time.

Twenty-first century resilience is not just about risk management.