Ten years ago, in a casual side conversation at Samsung’s headquarters in Suwon, a senior supply chain executive told me that the electronics giant was starting to move its manufacturing out of China and into Vietnam. The comment had a portentous ring to it. China, despite its air of inevitability, wasn’t the final answer to a winning global manufacturing strategy. Vietnam, right across the border, was at least part of the strategy and Samsung was placing a long-term bet.

Now, it looks like they played it right.

Why Re-Shore When You Can Next-Door?

Samsung’s proximity to and history with China may have been an important influence on the decision to enter Vietnam. Seoul is just 31 miles from the North Korean border, and at times the city is blanketed with a hazy sky full of China’s industrial emissions. Plus, the demographics and politics of China since 1980 point to a reckoning as hypergrowth slows. Unbeatable manufacturing capabilities perhaps, but with good reason to worry about putting all your eggs in one basket. So, Samsung methodically started the transition.

In contrast to Apple, whose mega-bet on Chinese manufacturing had paid off handsomely, Samsung never stopped owning and operating their own factories. This meant that it could navigate the complex cost/risk calculations of scaling up skills and automation as it expanded operations in Vietnam directly but incrementally, learning along the way. Much lower labor costs, ready access to component supply sources in Shenzhen, and relatively easy oversight from HQ in Korea combined to give Samsung’s supply chain team a smart, low-drama way to diversify away from an overweight dependence on China.

All the Right Moves

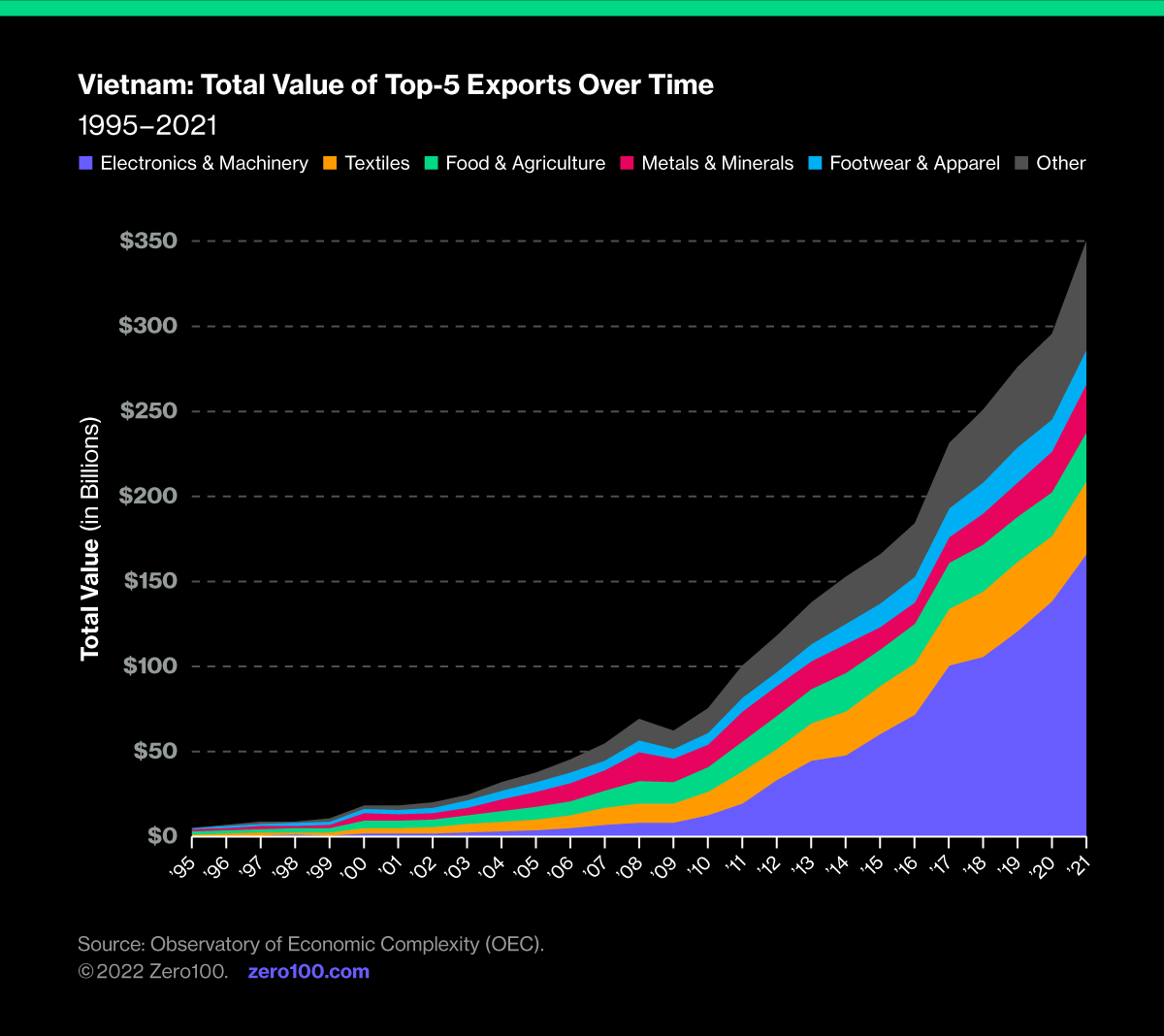

Meanwhile, Vietnam was laying the groundwork for its pitch as the next hot spot for global manufacturing. The country’s leaders have joined at least seven free trade agreements starting with a Bilateral Trade Agreement with the United States that went into effect in 2001. Along the way, deals have been struck with everyone from the EU to the PRC, amply demonstrating Vietnam’s willingness to do business.

It’s infrastructure has also been a focus with investments in road, rail, and seaports adding logistics resilience to its industrial hubs and natural advantage as a country with abundant coastal access to the South China Sea. Three of the world’s 50 busiest ports are in Vietnam including Ho Chi Minh City (slightly smaller than New York/New Jersey), Hai Phong, and Cai Mep, which together grew volume 15% between 2020 and 2021 while much of the world was flat.

Maybe even more important, as global brands gear up to comply with impending sustainability regulations, Vietnam has led the region in development of renewable energy sources. According to the Economist, “[Vietnam] has quadrupled its wind and solar capacity since 2019 … primarily the result of political will and market incentives.” Not a huge deal yet, but once the EU starts enforcing its Scope 3 disclosure requirements on consumer items, “Made in Vietnam” could become a prestige label.

Now Is the Time to Double-Down on Vietnam

Despite all that, Vietnam is now experiencing a significant economic slowdown (3.3% GDP growth Q1 of 2023 vs. 8% for full-year 2022) and a 6.3% year-over-year drop-off in industrial production for the first two months of the year. Plus, the President resigned in January over a corruption scandal dating back to his 5-year term as Prime Minister.

So why is Samsung investing billions of dollars higher up the value chain in semiconductor manufacturing and core R&D? Maybe because they are patient enough to see through the short-term dip in production that probably has more to do with bloated inventories of shoes and consumer electronics already in the US, than with any fundamental weakness.

In fact, this summer may be the perfect time to open conversations with Vietnam’s development representatives who may be more ready than ever to discuss tax breaks or investment incentives. Dell, Google, Microsoft, and Foxconn are already there, as are apparel leaders like Nike, Adidas, and North Face.

Moving to Vietnam for manufacturing is no quick fix for diversifying away from China. But for those willing to play a long game, Samsung shows it can be done.