Germany Pumps the Breaks on EU Regulation

The Corporate Sustainability Due Diligence Directive’s definition of supply chain accountability spans everything from labor standards to biodiversity, making compliance nearly impossible in the short term. Maybe Germany thinks perfect is the enemy of good as it refuses to support this proposed regulation.

The EU’s latest supply chain regulation, CSDDD, which was to be put to a vote on February 9, just hit a big hurdle. Germany, the biggest economy in the EU and a longstanding champion of integration, said it won’t support the regulation, forcing the Belgian EU Presidency to postpone the vote. Along with Italy, which was also expected to abstain, this is enough to freeze CSDDD in its tracks.

Good.

Brussels Overreach Hurts

Regulation is necessary, to be sure. Consumer health, economic fairness, and environmental sustainability are not natural outcomes of totally free markets. We learned this lesson painfully in the early twentieth century as robber barons crushed small businesses, exploited workers, and made a mess of much of the planet. And yet it is possible to have too much of a good thing.

The CSDDD includes too broad a definition of supply chain accountability, spanning everything from labor standards to biodiversity. It also double-counts EU carbon labeling regulations due to take effect in 2026. Plus, it applies to all businesses, private or public, with EU sales above €150M. If passed as is, this new regulation would put virtually all businesses currently selling anything in immediate violation.

Germany’s FDP party rightly complains that this is unduly burdensome to business and would hinder growth. They should know. The German economic engine driving Europe has been working in reverse the past few years as rising energy costs and slowing international trade combine with regulatory overreach to make life very hard for the legendary Mittelstand. Businesses in Italy’s structurally similar economy recognize the same problem and are standing with the Germans.

Supply Chain’s Butterfly Effect

A butterfly flaps its wings in the Amazon and a hurricane makes landfall in Texas. This catchy thought experiment is meant to convey the amazing degree of connectedness in our world. For supply chain leaders, the concept is all too real and much deeper than ordinary people (including government officials) can really understand. The iPhone, for instance, has materials sourced from suppliers in 43 countries, which collectively travel 500,000 miles before being sold in an Apple store.

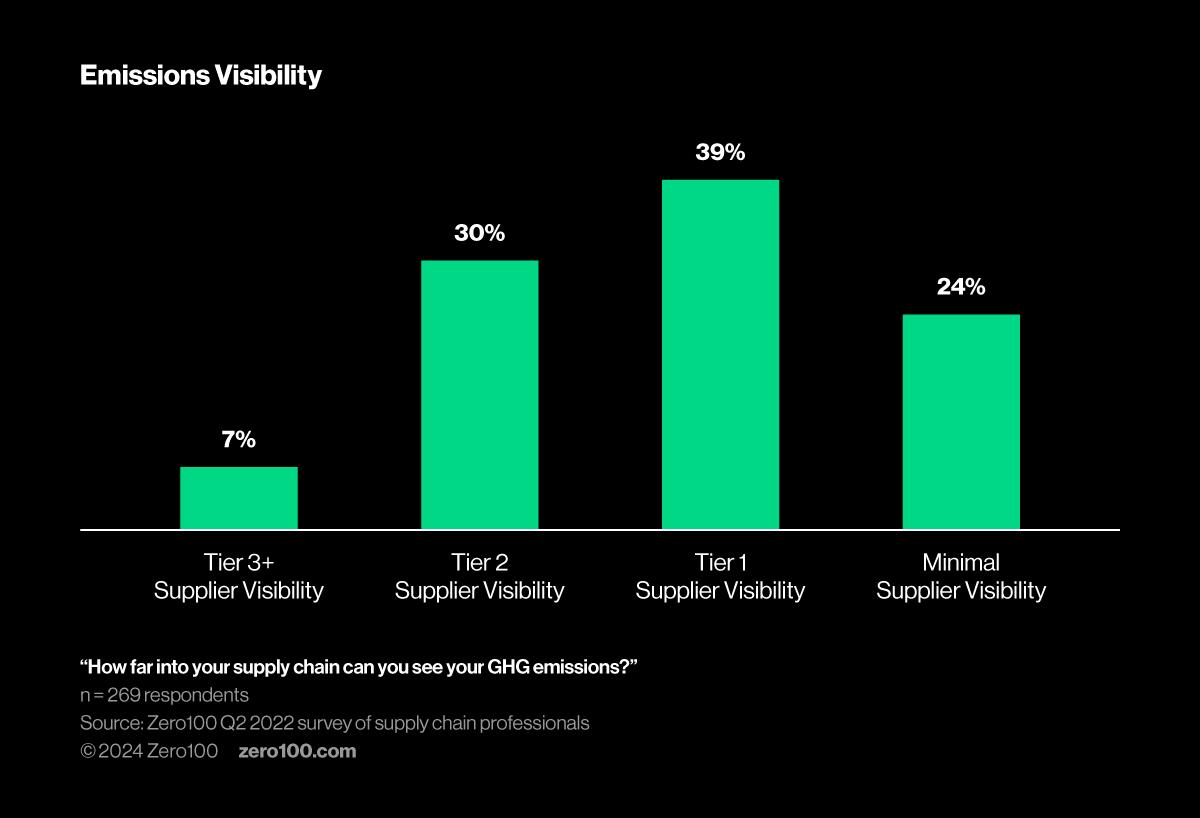

Zero100 data on supply chain visibility confirms the long-known challenge of seeing what’s happening three or more tiers back in any given supply chain. And it’s not for lack of trying. Since Covid, no topic has been hotter on CNBC than business’ resilience to supply chain shocks. Tech investments to fix this problem naturally help with measuring sustainability impacts, too, so the foundations for scaling supply chain accountability are being laid right now.

Yet heroic efforts made by big European companies, like Unilever, H&M, and IKEA, to take proactive responsibility for upstream impacts have more often been met with accusations of greenwashing than appreciation, let alone applause. One natural response of such businesses is to go quiet, aka “green hushing,” which works against our intent to save the planet by inhibiting industry-wide learning and consumer engagement.

Plus, forcing standards on suppliers upstream can clash with the business goals and local regulations of companies in countries outside the EU. What, for example, is an appropriate maximum workday? Or a reasonable minimum age for employment? Assuming Brussels knows best could end up gutting the fortunes of a factory owner in Bangladesh or a farmer in Mexico and, in the process, push workers’ families to emigrate north.

Unintended Consequences

I agree with the intent of the CSDDD but worry that it will do more harm than good. A cautionary tale with the same regulatory root is the Amazon-iRobot deal collapse. EU anti-trust regulators, worried about “competition in the market for robot vacuum cleaners,” scuttled the acquisition. iRobot promptly fired a third of its workforce and looks dangerously close to death.

The EU may not care about 350 employees in Boston, but they should care about the chilling effect this story has on future investment. Having blown the exit for founders, key employees, and venture capitalists, this regulatory intervention will likely dampen future investment. That may sound appealing to social and environmental activists, but it’s hardly inviting for anyone hoping to raise living standards while solving our sustainability problem with innovative technology.

Let’s pump the brakes on this one.