DfX Is the Key to Circular Supply Chains

Early decisions on materials, production processes, and use cases determine most of a product’s environmental impact – however we are still talking about Design-for-X as a new discovery. Perhaps the problem is more about habits and conflicting goals than a lack of engineering foresight.

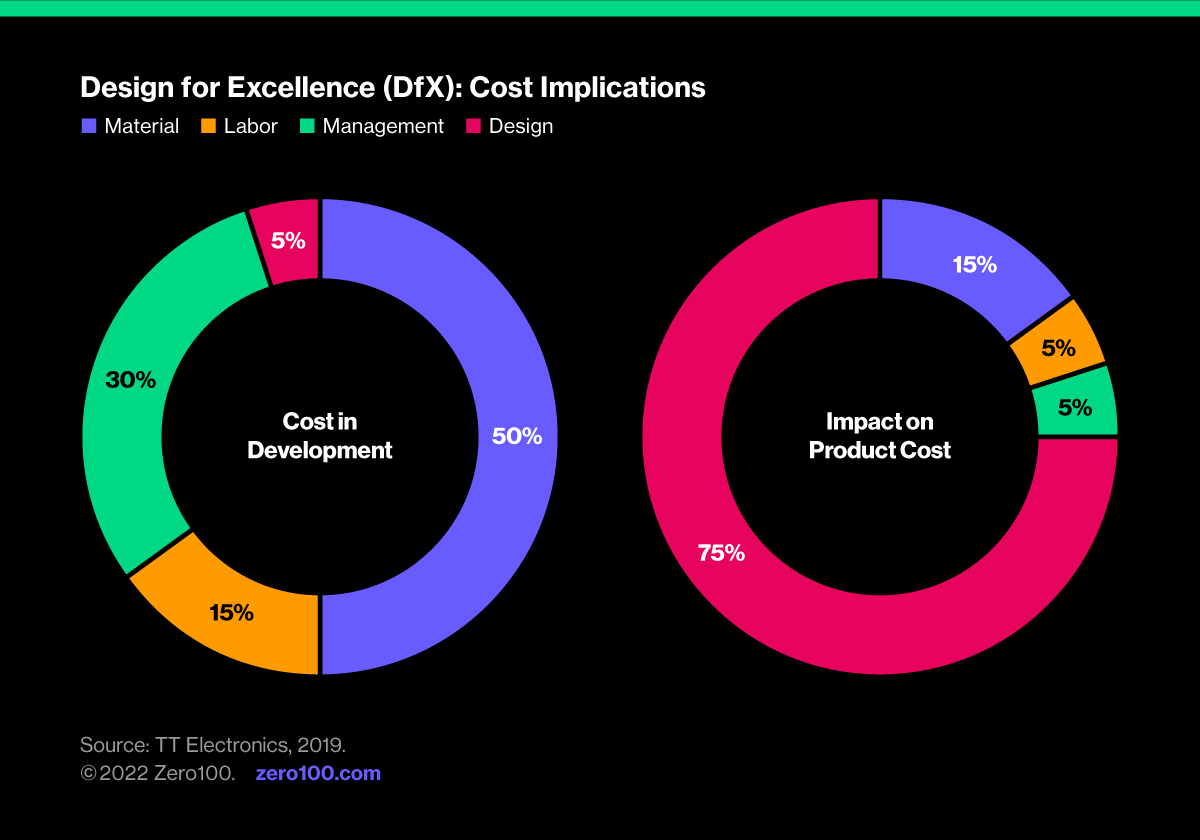

There is an old truism that 70-80% of a product’s lifecycle costs are locked in during design. The European Commission cites this figure calling for sustainability in up front design in its 2020 Circular Economy Action Plan. The original source of this factoid may have been a 1960’s DARPA engineering study, but its logic is inescapable: the early decisions on materials, production processes, and use cases determine most of a product’s environmental impact.

Grasping this principle might seem a powerful unlock for leaders eager to improve the sustainability of their operations, and yet here we are, sixty years later still talking about Design-for-X as though it’s a new discovery. Perhaps the problem is more about peoples’ habits and conflicting goals than a lack of engineering foresight.

Different Roles, Different Goals

People working in design, R&D and product engineering functions typically favor the thrill of innovation. Most would rather do something new and exciting than go back to the drawing board to cut costs on someone else’s design.

Meanwhile, circular economy devotees are constantly looking for ways to reduce, reuse, and recycle everything that’s already out there. They push for right-to-repair rules to extend the useful lives of machines and electronics, as well as takeback guidelines on packaging meant to increase recycling.

Operations sits in the middle trying to make ends meet with notoriously bad returns, supply chains, minimal post-consumer material sourcing, and fragmented service and spare parts networks. The supply chain mission of cutting costs while improving service is still in conflict with the complexities of new product launch and aftermarket support.

Until these very different roles start playing by some shared rules, DfX will not achieve its potential in circular supply chains.

Business Model Innovation Helps

IKEA is well-known for its design prowess, not only in terms of the look of its stores and furniture, but also its supply chain which coopts customers to handle most of its last mile logistics and final production. DfX in an IKEA context includes design for good quality, low cost, ease of assembly, and sustainability.

The business model is not really retail so much as living space solutions for homemakers. By designing for the moment a customer gleefully sits down at their new dining table, IKEA’s business model enables most of its product lifecycle goals. Adding circularity to this DfX equation is natural since its creatives, operations people, and sustainability leaders are all chasing the same idea of success.

The same could be said of Tesla whose DfX principles start with enabling electric vehicles and a full ecosystem engineered as part of the value proposition. This includes an entirely new battery supply chain, an extensive charging network, and a cloud-based system for updating electronic systems on what is essentially a giant iPhone on wheels.

The company is not really a car maker so much as a lifestyle trophy for gadget lovers. Again, the business model shift is part of why Tesla could unite so many players in a common DfX mission. The recent recall which Tesla fixed with a software patch over the cloud was a perfect proof point of its DfX capabilities, and the power of its business model.

Can Your PDM System Handle the Job?

Technology is indispensable to DfX, regardless of whether X stands for manufacturability, service, or circularity. Everything from compute-heavy 3D CAD systems and manufacturing simulations to lifecycle analysis tools and telematics need to be tied at the unit level. Old-school Product Data Management (PDM) systems developed by CAD vendors like Dassault Systemes and PTC have evolved around this compelling vision.

Unfortunately, few business users have had much luck with the more ambitious of these initiatives, so the foundational tech for connecting all this product information to decision-makers in design, supply chain, service, and sustainability largely isn’t there.

Best-in-class PDM systems are mostly found in automotive and aerospace where program leaders enforce DfX principles holistically, like IKEA does. Plus, high price tags justify detailed lifecycle engineering.

Look to transformational automakers like Volvo, General Motors, and BMW for leadership on circularity. They have the most to gain by doing it right, and the scars from doing it wrong as they learned.